Holocaust Archives - INTO THE LIGHT

Holocaust Survivor’s Art Kept Him Alive

On , | No Comments | In Blog, Holocaust, Uncategorized | By

In honor of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, I share Saul Gonzalez’s recent interview with Kalman Aron on Public Radio International’s broadcast, The World. Saul visits Kalman at his L.A. studio and learns how art has kept him alive, not just during the Holocaust, but throughout his lifetime.

“When you step inside artist Kalman Aron’s modest apartment in Beverly Hills, a lifetime of creation surrounds you. The walls are covered in paintings and finished canvases are stacked on the floors, a dozen deep. The paintings range from portraits to landscapes to abstract works. They’re just a fraction of the roughly 2,000 pieces Aron says he’s created over the decades.”

Click on the image below to listen to the full broadcast:

Kalman Aron, survivor of Nazi camps, featured in Jewish Journal

On , | No Comments | In Blog, Holocaust, The Artist, Uncategorized, Videos | By

Kalman Aron’s story continues to be heard. Eitan Arom of the Jewish Journal writes about Aron’s remarkable past and the comfort he finds currently in art to soothe the loneliness he is experiencing at the age of 92:

“Apart from his wife and a part-time caretaker, it’s his paintings that keep him company.

‘I don’t have anybody to talk with,’ he said. ‘All my friends are gone. I had probably 15 friends. They were much older than me. I was the youngest one. And then suddenly, nobody here. I have drawings of them. A lot of drawings in the back there. Filled that room downstairs, filled up completely.’

At the age of 92, Kalman Aron is very much alive. The article quotes him as saying:

“’Friends of mine, they get old and they don’t know what to do, and they die of boredom,’ he said in his dining room, his eyes widening with intensity. ‘Boredom! And I’ll never die of boredom, as long as I have a piece of paper.'”

Kalman continues to be as dynamic as the light and color in his paintings. To read the full article, click here.

Interview: Dr. Margers Vestermanis, Holocaust Survivor, and Author Susan Beilby Magee

On , | One Comment | In Holocaust, Riga, Riga Holocaust, Uncategorized | By

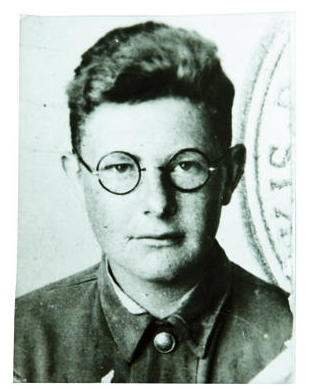

Dr. Margers Vestermanis, founder of the Museum and Documentation Center “Jews in Latvia.” (photo: Wikipedia)

In honor of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, I share a recent interview with Dr. Margers Vestermanis, Holocaust survivor, historian and expert on the history of Jews in Latvia. Born in Riga in 1925, he endured the horrors of the Holocaust. He escaped from the death march from the Dundaga concentration camp to the sea in the summer of 1944 and joined a group of partisans in the forests of Northern Courland until the war ended. After the war, he studied history in Riga, earned his PhD, and became an archivist in the State Historical Archives. He was dismissed in 1963 for writing a paper about the Holocaust, and he then worked as a high school teacher for many years. In 1990, following the Independence of Latvia, Dr. Vestermanis founded the Museum “Jews in Latvia” and served as its first director for many years.

I first met Dr. Vestermanis in Riga in 2004 when I was researching Kalman Aron’s life for my book—INTO THE LIGHT: The Healing Art of Kalman Aron. He kindly agreed to an interview in his office at the Jewish Community Center in Riga. Ten years later, I returned to Riga to present Kalman Aron’s story at an international conference at the same Jewish Community Center. Dr. Vestermanis agreed to a second interview to reflect on his experience and what he learned about human nature.

His responses to my questions are powerful, profound and insightful. I thank Dr. Margers Vestermanis for letting me share them with the world.

During the Holocaust, about 70,000 Latvian Jews lost their lives. Dr. Vestermanis has devoted his life to preserve the memory of Jewish life and culture in Latvia. He remains a vibrant voice, reminding us to “never forget.” I honor him and welcome your responses which I will share with him.

______________________________

Magee: What words can you use to describe the evil you experienced and how it affected your heart and soul?

Vestermanis: It was the first time that we felt outcast; we felt that our pain and the torture of death hardly disturbed anyone. It did not matter neither to our local society, nor to the rest of the world. This injury we, as individuals that survived the Holocaust and as the Jewish society as a whole, will harbor in our souls until the end of the days.

Magee: What is your understanding or view of human nature in general?

Vestermanis: A human is an egoist by nature. Love to our family and relatives, as well as friendship, should be brought up by our family members, teachers at school, and, in the end, by the society and the state. Of course, even the inveterate egoist feels the necessity of doing something good, positive, but usually this spontaneous glimpse is extinguished by arguments and ice-cold calculation.

Magee: What have you learned about your own nature?

Vestermanis: It is said, that a human comes from his or her childhood, from ancestral home. I come from a family focused on German culture that would decline even thoughts of possible assimilating. In contrast, there was cultivated the feeling of Jewish national pride for our input into civilization and culture. Since I was six years old, a private Rabbi taught me the Holy Scripture and other ancient Jewish books that were perceived in my family not as religious tenets, but mythological basics of our national culture. This sense of significance of our people, high national self-consciousness was, with no doubt, the most important and decisive aspect that helped me to survive the Holocaust.

Magee: How did you survive? What resources within yourself did you use to survive?

Vestermanis: Surviving the Holocaust was a mere accident. I was young, physically strong, and, what is the most important, I saved the will to resist. After several unsuccessful attempts to escape, an accident helped me: the concentration camp Dundaga, where also Kalman Aaron was held, due to the approach of the Red army in the end of July in 1944 was moved in a strong pace of “death march” to ports in Liepaja and Ventspils. Many people died on the way, but when our path ran through the forested place under Ugale, many people made the last effort to jump over the ditches on the sides of the road and rushed to the forest. I was one of them. I managed do join the antifascist partisan troop of Latvian people, who did not want to join the SS legion. In our troop, there were also soviet prisoners who escaped from German camp and even one German deserter (defector) Obergefreiter “Luftwaffe” (driver of anti-airforce artillery) Egon Klinke, who became my friend later.

The western side of Latvia later transformed into “Courland pocket”, where the Red army locked about 300 000 German soldiers – 16th and 18th Wehrmacht armies that could not escape from the “pocket” up to 9 may 1945. During this time the armies hurled all effort into going through forests searching for those who escaped, and on the 26th of December our troop was destroyed. My German friend Egon and I were among the few people that managed to break through, but after 5 days – on the New Year night of 1945 I lost my friend too, and until 9 may 1945 I was wondering around the forest as an “armed partisan loner”. I would like to highlight that without help from a friendly part of Latvian people I could not survive in the forest during the time of “Courland pocket”. Professor of the University of Jerusalem Dov Levin, historiographer of the resistance of Baltic Jews, writes: “Marger Vestermann was the last Jewish partisan of the World War II, who met the day of German capitulation going out of the forest with weapon in his hands.” This is only partly true – one more armed partisan was the other former prisoner of Dundaga concentration camp Jakov Rossein, who has already passed.

Magee: How did the Holocaust inform the choices you have made in your life since and how have you found meaning, given the experience?

Vestermanis: I would like to answer your fifth question with the words of the great “hunter of Nazi war criminals” Simon Wiesenthal. He writes: “When I will die and fall into another world, the millions of souls of killed Jews will surround me and ask: “What did you do with your life, that you managed to save?” I could answer in many different ways, but I will tell them the most important thing: I did not forget you! (ich habe euch niche vergessen)!” Of course, it would be a sacrilege to compare myself with the famous Wiesenthal. However, his words were “credo” of all my “post-Holocaust life”: I devoted myself to preserving the memory of the world of Latvian Jews that died in horror, tears and seas of blood. This duty, this mission will not leave me until my last breath. And I am happy that it so happened.

Magee: How are Riga and Latvia different today? How are they the same?

Vestermanis: Latvia and Riga had never known brutal anti-Semitism; however, it existed, and still exists, in a latent form. Our major difference is that currently the recognition of our suffering is not enough, we demand the principal condemnation of those who are guilty, “our” murderers, a part of which as “displaced persons” escaped the responsibility on the West. The other part of them was arrested and condemned by the Soviet authorities of KGB, not always objective. Their families also suffered, they were deported to Siberia. Guilty or not – all of them are considered victims of the “red terror” and national martyr, to which are dedicated monuments, museums and so on. They use their special status. This inability and unwillingness to deal with the dark spots of national history are “neurological sensitive points” in our, in fact, good relationships.

Magee: What wisdom/what message do you wish to give the world and particularly to the children…to your grandchildren’s generation?

Vestermanis: To the children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren – to learn to live together, in peace. Peace is the main thing that our ancestors were dreaming of, and what we, the generation that went through all the flames of hell, bequeath to the entire world and to America as well.

Magee: What message do you want me to take home to Kalman Aron in America?

Vestermanis: I wish him – take it easy, my friend! Search for the last, the most important theme. For me it is still Holocaust.

My cousin, who subsequently survived in concentration camp Buchenwald, Boris Lurne, and who later in the States became one of the “apostles” of a new art movement called “No-art” shortly before his death sent me a large poster – on the black background with a yellow paint was pictured something strange, scary and unimaginable, like a nightmare. This work he dedicated to our common, eternal theme – Holocaust. In my opinion, it is the most exact attempt to deliver graphically to the consciousness of people something that can be called “unimaginable”. Good luck, my friend!

© 2015 Susan Beilby Magee

Riga, Latvia 23 November 2014

On , | No Comments | In Holocaust, Riga | By

After spending a few days in St. Petersburg, I flew back to Riga, Latvia, yesterday. On the plane I asked myself how I felt, returning after 10 years. Part of me does not want to look again at what happened here over 73 years ago. My breath was shallow, and I felt like I was physically bracing myself for this visit. I plan to go to Kalman Aron’s home, the ruins of his neighborhood synagogue, the ghetto where he was imprisoned for 2 ½ years as well as the killing fields in Rumbula forest where his mother, Sonia, was killed with 25,000 other Riga Jews on 2 days in 1941. So I ask myself:

How do I ground myself and stay fully in my body?

How do I honor and hold all involved—the victims and the perpetrators—in light and love?

How do I heal the fears, shadows and darkness in my own body and transmute them into light?

I do not know the answers. I think this is a practice. But I am ready to see the places that defined Kalman Aron’s life.

I first visit his home on 40 Moscow Street. I looked and looked for it ten years ago, but I only had a description: a 5-story building with a courtyard and a two-story building at the back of the courtyard, facing the Daugava River. Kalman lived on the second floor at the back, overlooking the river. I found it today. It is in the photo across the street from me where a man is entering the five-story building. I walked around the back and saw the small building where he lived and I saw the window Kalman looked out across the river to an island where his first “love” lived with her mother. He proudly took her to a ball at the his art school, the Riga Fine Arts Academy. After the Germans entered Riga on July 1 of 1941, he snuck across the river to the island to see if they were OK. The small home was empty. Mother and daughter were gone, never to be seen again.

I next go to the memorial for the Choral Synagogue in Kalman’s neighborhood. Several hundred Jews, hiding from Lithuania, were burned alive when the Nazis locked the doors and set it on fire. Kalman saw the flames. Since I was here in 2004 a new white monument has been built to honor the Latvians who risked their lives to save Jews by hiding them in their homes. Throughout Latvia 729 Jews were hidden, of which 544 survived. In Riga alone 256 were hidden, of which about 200 survived. Janis Lipke, who saved over 50 Riga Jews, is listed on this monument as well.

I then stop at the Old Jewish Cemetery. Founded in 1725, it was the first Jewish cemetery in Riga. By the end of the 1930s it was full. On July 4, 1941, when the Nazis burned all but one synagogue in Riga, they burned the buildings associated with the cemetery. They later buried in mass graves Jews who died in the Riga ghetto. Today it is a park although stones remain from old graves.

After having lunch, I go to Ludza Ilea where Kalman, his mother, Sonia, and his older brother, Henech, were imprisoned in the Riga ghetto. Eight thousand, mostly Russians, lived in the 8-block area. The Nazis moved them out and moved 30,000 Riga Jews into these small two-story wood clapboard houses. Kalman shared one room on the second floor with his mother and brother. The ghetto was closed in September of 1941, and every day he had to walk through the guarded gate to go to work and to return. A photo below shows me looking at a map of the ghetto on Ludza’s street where they lived with my interpreter, Victoria. The other photo shows the entrance to the ghetto during the war. I walked these streets in 2004, but I only recently found his address on Ludzas Iela 75/77.

Finally, I drive to Rumbula forest where Kalman’s mother was brutally executed along with 25,000 other Jews in 1941. This is the most difficult visit. Today there is a memorial amidst the large trenches the Nazis prepared for the Riga Jews. They lined the prisoners up in single file; told them to put their shoes in one pile, their clothes in a second one and walk to the trenches. They were then told to lie down in the trench where they were shot, and as one layer of people was executed, a second group of human beings were told to lie down on top, and of course they were then shot. This continued the afternoon and early morning of November 29/30 and then again on December 8. We know exactly what happened because a young girl, Frida Michelson, dropped down in the shoe pile, hiding; then waited until it was safe; and she returned to the ghetto to report what had happened. She wrote the book: I Survived Rumbuli.

In 2004 to honor of Kalman’s parents, Claim and Sonia, I arranged to have a stone placed with their names engraved at this memorial. I have a photograph of it, but today I could not find it. It was hard to read the engraving on the stones damp from fog.

As I stood on this ground, I focused on Kalman’s gifts and legacy. His parents can be proud and grateful that he survived and maintained his integrity; that he was faithful to his muse, creating art; and that he found peace in his 9th decade after choosing to tell his story. I honor him, all his kindred spirits who survived and those who died in the Holocaust. May their sacrifice invite us all to resolve human conflict peacefully and no longer resort to killing as a solution to anything.

Photos ©Nikolajs Krasnopevcevs 2014

IK “Froggy Studio”

© copyright Susan Beilby Magee, 2014